Those Remembered (and Forgotten)

The stories of three winemakers in Cornell's Eastern Wine & Grape Archive.

During a road trip in July, I made a last-minute detour to visit the Eastern Wine & Grape Archive at Cornell University. I had already begun working on this piece when I learned that August was Finger Lakes Wine Month.

With no particular agenda, I requested the materials that caught my eye, focusing on three men: Isaac Purdy, Philip Wagner, and Raymond Fedderman—two of whom were White and one Black. Tracing their stories was a mere glimpse into how power and privilege have played a role in our collective memory of American wine.

I wish, at that point, I had the work of historian Tiya Miles for reference. Her scholarship later brought context to the tension I have felt while searching for remnants of Black winemaking in the archives. “These records were created by fallible people rather like you and me,” she writes. “Even in their most organized form, archived records are mere scraps of accounts of previous happenings, ‘rags of realities’ that we painstakingly stitch together to picture past societies.”1

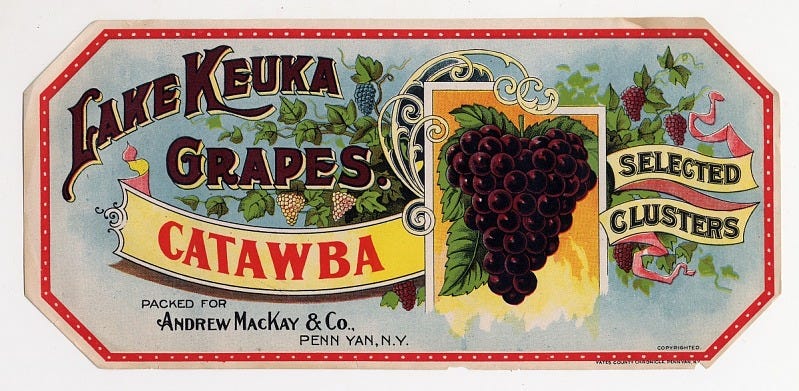

My visit to Cornell’s archives certainly involved many scraps, and because all three men were no longer living, there were more questions than answers. I started with the materials from Isaac Purdy (Man #1), one of the region’s first growers to sell grapes commercially in the late 1850s. For decades, he jotted down the events of his day-to-day life. The archive holds 16 of Purdy’s journals from 1867 to 1910.2 Based on the ones I thumbed through, he and his son, Fred, often spent the first day of the new year pruning their Catawba vines.

There’s also a copy of The Chronicle Express’s 1974 summer issue, in which a reporter used Purdy’s journals to recount the rise of New York’s first grape boom.3 “Dwellings, barns, and fruit houses have all been built with money from the sale of grapes,” Purdy wrote in 1909.4 He and other growers in Penn Yann, the town north of Keuka Lake, sold their grapes (Catawba, Delaware, Isabella, and others) as far as Baltimore, Maryland.

On the heels of Prohibition, Baltimore would become synonymous with Philip Wagner (Man #2), one of the Eastern wine scene’s foremost names during the 20th century. Like many people, he started as an amateur grape grower and home winemaker. By the time Congress repealed the 18th Amendment, Wagner was an editorial writer for The Baltimore Sun and had published his first book: American Wines and How to Make Them.5 He’d go on to be the newspaper’s editor, live abroad, and publish more books—a wine writer’s dream career.

Wagner was a fervent proponent of French hybrid grapes (So much so that in the 1940s, he started a nursery and winery dedicated to such varieties). After World War II, a proliferation of small-production wineries would “change the face of American winemaking,” according to one wine historian. “It is enough to say that without Philip Wagner and the French hybrids, this would not have happened in the eastern states.”6 Boordy Vineyards still exists, though the Wagners sold it in 1980.7

It should be noted that Wagner’s estate was one of the original benefactors of Cornell’s Eastern Wine & Grape Archive, ensuring his memory would be preserved. The Philip Wagner Papers hold 16 boxes of letters, manuscripts, winery records, and photographs. Wagner’s materials reveal the breadth of his influence: From a letter he received on the Concord grape research being done at Cornell’s Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva, NY, to a cautionary speech he gave to Virginia winegrowers, who were steadily abandoning American native and hybrid grapes for Europe’s Vitis Vinifera.8

I wonder if Wagner and Raymond Fedderman (Man #3) ever crossed paths since they had mutual friends in the Finger Lakes. Based on the western outskirts of Keuka Lake, Fedderman promoted himself as owning the first Black winery in the United States. He was likely the first to do so in New York, but unbeknown to him, Virginia’s John June Lewis had already been operating Woburn Winery for three decades (Pictured above).9 Fedderman Wine Company lasted a single vintage before the trouble started, and the banks withdrew their loans.10

In Cornell’s archives, a manila folder contains the advertisement for Fedderman Wine Company and two of its labels: A white blend and a fruit wine made from watermelons and peaches.11 There’s also a page from Emerson Klees’s pictorial book about wineries in the Finger Lakes. It shows Fedderman shaking hands with Robert F. Kennedy in 1967, a year before the senator was assassinated.12 They’re standing in a row of sprawling vines, likely at Bully Hill Vineyards, where Fedderman spent much time before starting his own winery.

Locally published articles, like one from the Vineyard View, provided some of Fedderman’s origin story. Born in Virginia, he was a former sharecropper who migrated to New York and had some success as a potato farmer before breaking into the wine industry. The man had big dreams. He wanted to build a winery large enough to produce 50,000 gallons of wine—what would have been ten times larger than Woburn Winery.13 Based on what we know, that never happened.

I can’t help but think how Fedderman was forced out of business three years before New York’s Farm Winery Act of 1976, which would allow small wineries to more easily produce and sell wine.14

Fedderman isn’t the only Black winemaker to have lost his winery or vineyards. In 2015, California’s Sterling family was forced to surrender Esterlina Vineyards under similar circumstances.15 More recently, winemaker Krista Scruggs of ZAFA Wines acquired 56 acres on Vermont’s Isle La Motte, where she planted vines.16 However, the state ordered a cease-and-desist after discovering that Scruggs was producing and selling wine without the proper licenses.17 For unknown reasons, she has since moved ZAFA’s production to Wisconsin.

After leaving Cornell, I wondered how all three men (Isaac Purdy, Philip Wagner, and Raymond Fedderman) were remembered beyond the archives. In Thomas Pinney’s two-volume book, A History of Wine in America, Wagner is one of the leading characters while Purdy and Fedderman appear in neither.18

“Some wineries have opened and closed leaving little trace of their existence,” writes Hudson Cattell in Wines of Eastern North America.

He’s referring to Fedderman and John June Lewis, who many historians have further tokenized as the first Black Americans to own a commercially bonded winery. In Cattell’s version of their story, Lewis’s Woburn Winery “closed sometime after World War II” and “had long been out of business” before Fedderman Wine Company appeared.19 However, even this information is disputable, as records from the Alcohol, Tobacco Tax, and Trade Bureau show that Woburn Winery was bonded until 1977—three years after Lewis died.20 The only source that Cattell cited for Fedderman was an article about the winery’s closure in 1973.21

I wanted to know what happened to Fedderman.22 Unfortunately, tragedy continued knocking on his door. In 1983, the Fingers Lakes region had one of the heaviest snowstorms of the century. Fedderman and his wife, Irene, lost their 13-year-old son in a sledding accident that winter.23 Then, the patriarch himself died the following year—a decade after the closure of his winery.24 It’s a bitter note to end on. Still, I feel some solace, having learned more than what the wine world has chosen to remember, or forget, about Fedderman.

There’s only so much we can learn from the archives. That’s why I’ve turned to other historians, like Tiya Miles, whose work might be able to teach us how to tell these lesser-documented stories. I’ll leave you with her words:

“To abandon these individuals, the ‘archivally unknown’ who fell through the cracks of class, race, and position, would consign them to a ‘second death’ by permitting their erasure from history. It would also mean turning our faces away from fuller, if unwelcome, truths about our country and ourselves.”25

Correction: According to the director of Bully Hill’s Greyton H. Taylor Wine Museum, the man depicted in Emerson Klees’s book, Finger Lakes Wineries: A Pictorial History, is not Raymond Fedderman but a worker of the former Widmer Winery.

Tiya Miles, All That She Carried (New York: Random House, 2021), 27-28.

Purdy Family Diaries, #3797. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Unknown Author, “Family Diaries Provide History of Commercial Grapes in Area,” The Chronicle Express, Summer Issue 1974; Purdy Family Diaries, #3797.

Isaac C. Purdy, “Reminiscences,” Yates County Chronicle, April 7, 1909.

Frank J. Prial, “Philip M. Wagner, 92, Wine Maker Who Introduced Hybrids,” New York Times, January 3, 1997.

Thomas Pinney, “Philip Wagner and the French Hybrids,” A History of Wine in America, Volume 2 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 189-191.

Philip Wagner Papers, #6928. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Note: The first time that I came across this photograph was in a presentation on the history of Virginia wine, given by Erin Scala, the owner of Market Street Wines in Charlottesville. Thank you for everything, Erin.

Frank J. Prial, “For the ‘First Black Winery in the U.S.,’ 1973 Was Not a Good Year,” New York Times, November 16, 1973.

Fedderman Wine Company Advertising Material, #8064. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Emerson Klees, Finger Lakes Wineries: A Pictorial History (New York: N.P., 2014).

Unknown Author, “Profile of Raymond Fedderman,” Vineyard View, Vol. 2, No. 1, December 1971; Fedderman Advertising Material, #8064. Note: The newsletter was published by Bully Hill’s Wine Museum from 1969 to 1988.

“New York Wine Reference Guide,” New York Wines, last modified January 2022.

Bill Swindell, “Black founders of Healdsburg's Esterlina Vineyards accuse bank of discriminatory lending,” Press Democrat, June 20, 2016.

Krista Scruggs, “This Land is My Land,” Food & Wine Magazine, March 22, 2021.

Ellie French, “Burlington wine maker sought investors, but didn’t have a liquor license,” VTDigger, November 23, 2020.

Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America. Note: Throughout the book, Philip Wagner is mentioned on 15 occasions.

Hudson Cattell, Wines of Eastern North America, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014), 84.

Bonded Wineries Lists 1936-1988, Cornell University.

Frank J. Prial, “For the ‘First Black Winery, 1973 Was Not a Good Year.”

Note: Thank you to Elaine Chukan Brown, award-winning wine writer and communicator, who took the time to search their copy of Pinney’s book before mine arrived in the mail. They then found the information regarding the deaths of Fedderman Jr. and Sr., respectively.

Unknown Author, “North County Spared in Season’s Worst Storm,” The Journal, January 17, 1983.

“Raymond Fedderman, 1915-1984,” Find a Grave, last modified February 2022.

Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 29.

So good. Love how your research mirrors contemporary efforts in farming and access. Like you said more questions than answers …but the scraps allude to hidden gems of innovation. Also… that watermelon peach ferment 😮💨👌🏽

Amazing work!!!